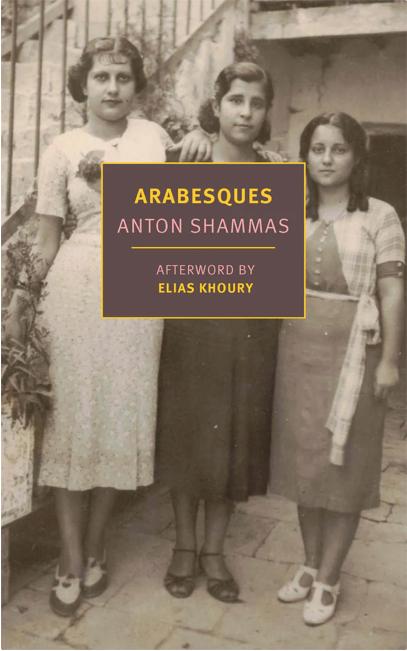

The sepia-tinted photograph on the cover of the new edition of Arabesques, Anton Shammas’ 1986 novel, depicts the author’s mother, Hélène Bitar, in Tyre, Lebanon, 1938. This family photo is the first of the documentary evidence Shammas uses to tease the reader. The factual nature of dates and events in the history of the Palestinians before, during and after the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, are accurate. So are many of the autobiographical details about the author’s own Christian Palestinian family and life. The narrator is even called Anton Shammas but he is thoroughly unreliable. His memory and imagination are interchangeable while the family members who are his main source of information sometimes confess to making up the whole story.

This “autobiographical novel” alternates between sections entitled “The Tale” and “The Teller”, stylistically different but equally fascinating and beautifully written. Although “The Tale” is told in a non-linear way, the scattering of dates and years act as guideposts to lead us back and forth through more than one hundred years of family history. In 1874 Shammas’ grandmother Alia was born in Lebanon (“in the year of the Ottoman law on growing tobacco”). In 1947, just before Israel was founded, Shammas’ father decided to invest all his savings in the family’s future in Haifa (a lease on a house and shoemaking equipment). He failed to anticipate that “he would bet his shirt and lose it on the State of Israel”.

The history moves through the years of the British Mandate (1920-48), the Arab revolt of 1936-39, evictions by the “Jewish army” and the mutual violence between Muslims and Christians. It continues up to the 1980s in the Palestinian village of Fassuta in the Galilee, the narrator’s birthplace, which ended up inside Israel when the state was founded.

Shifting between “The Tale” and “The Teller”, the narrator is on a quest to discover whether his namesake, the original Anton Shammas, son of his aunt Almaza and uncle Jiryes, really did die as a baby. That is the story he was told by his uncle Yusef. As if in a detective story he follows up leads, many of which are false. The loose ends are never tied up but that only makes this novel more intriguing.

Arabesques is reminiscent of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. In both inherited legends and family myths blend seamlessly with history and politics to tell a story that is both real and fictional. At first glance “The Teller” sections which take place in Paris and Iowa, where the narrator is on an international writers’ programme, appear to be a separate narrative. However, they soon intertwine with “The Tale” until they become one. Even the magical realism from the Palestinian Tale makes its way into the more western Teller sections.

Anton Shammas called Arabesques “an Arab story in Hebrew letters”. The question of language is important. Shammas was born in Israel, was steeped in Hebrew literature, ancient and modern (evident from all the references in his novel) although he studied English and Arabic literature at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. But writing a novel in Hebrew was not a matter of course; it was a political act. Arab Israelis like Shammas had Israeli citizenship but, because Israel is a Jewish state, he was deprived of having Israeli nationality (he explains how nationality is defined in Israel in his 1995 article “Palestinians in Israel: You ain’t seen nothin’ yet”). To write in Hebrew, the national language of the Jewish state, was to defy this state of affairs.

The intricate arabesque structure of the novel has parallels with the way Shammas sees the political situation. It follows the pattern of One Thousand and One nights, that quintessential Arabic tale, in which subsidiary stories grow from and weave into the main narrative. So the Jewish majority in Israel provides the framework while the Arab minority is subsidiary, although they both become intertwined. The ideal solution for Shammas would be the resolution of the arabesque: “in the end all harmonise together in a single arabesque”. Translated into a political solution this would be a non-ethnic, secular binational state.

Shammas wrote his novel before the first intifada (Palestinian uprising) in 1987. Three decades later he wrote “Why bother translating the Palestinian pain into the language that caused that pain in the first place”. His answer to that question is not optimistic: it resembles the futility of praying - you do not expect to get an answer but you go on anyway.

Arabesques by Anton Shammas was published in the New York Review Books classics series in January. It is translated from the Hebrew by Vivian Eden with an afterword by Elias Khoury.