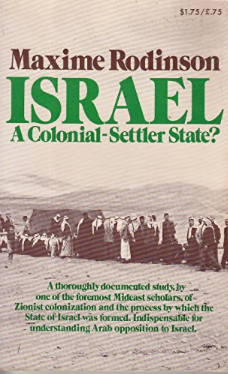

In Israel, A Colonial Settler State? (1973) Maxime Rodinson examined critically what colonialism and Zionism were, and who were the settlers. He concluded that Israel was a colonial-settler state. But his paradigm has little in common with the one entrenched in today’s post-colonial studies circles in universities and beyond. This is because, as Edward Said once said of Rodinson’s work, it is “responsive to the material and not to a doctrinal preconception”.

It is worth understanding the arguments Rodinson made in reaching his conclusion. His open-ended approach makes it a relevant book to read now, when so much of political thinking is done within a polarising framework. Rodinson’s idea of “the coloniser and the colonised” does not fit any conception of the world divided into simplistic either/or categories. It could even be argued that his critique undermines his own colonial settler paradigm.

Rodinson (1915–2004) was a respected French Jewish Marxist scholar in the field of Islamic and Middle Eastern studies. The original French version of Israel, A Colonial Settler State? was published in a 1967 special edition of Les Temps Modernes (a magazine edited by Jean-Paul Sartre and others) under the title of Le Conflit Israélo-Palestinien, just as the Six-Day War was ending. The English translation was published in 1973. They can be read as Rodinson’s dialogue with, rather than a polemic against, his contemporaries in the French left milieu and in the Arab intelligentsia of the 1960s.

According to Rodinson, what made early European Jewish emigration to Palestine a colonial process was its lack of regard for the people who already inhabited the land. This blind spot, says Rodinson, was because the European supremacy outlook made the indigenous people invisible to the emigrants. For Rodinson, it was colonisation albeit “with special characteristics”. For example, land was not stolen but purchased legally before and during the British Mandate. In addition, the emigrants, from 1881, escaping from oppression and pogroms, bore little resemblance to the British colonial types. He even praises the “collectivist colonies” that were set up in Palestine as “perhaps the most advanced example ever seen - of the virtues that can be developed by a communitarian life style inspired by humanist ideology” (p83).

There is little doubt that Theodor Herzl, the author of the Jewish State (1896), a seminal work which provided the programme for the Zionist project, was a leading representative of the colonial mindset. Even so, Rodinson saw this as unexceptional: “There is no reason whatsoever to be surprised or even indignant at this. Except for a section (only a section) of the European socialist parties and a few rare revolutionary and liberal elements, colonization at the time was essentially taken to mean the spreading of progress, civilization and well-being” (p42).

Rodinson put Herzl into context – he was typical of his class (bourgeois) and his times (the late 19th century). Rodinson also contextualised Herzl’s “conversion” from a secular Austrian Jew to a Jewish nationalist. This shift came, at least in part, after Herzl witnessed first-hand as a journalist the Dreyfus Affair in France. This involved the trial of a French-Jewish army officer accused of treason by an anti-Semitic section of the French elite. Hannah Arendt, a German-Jewish political theorist, called the trial and the surrounding furore “the dress rehearsal for the Nazis”.

Rodinson, while priding himself as the best-known anti-Zionist in France, did not fall into the trap of presenting a caricature of Zionism. He understood that Zionism was not a monolithic ideology. There were different strands competing with Herzl’s version. At the First Zionist Congress in Basel in 1897, Herzl’s Zionism did win but not without being bitterly contested. Rodinson recognised that throughout the period of the British Mandate in Palestine there was a large minority of the Yishuv (the Jewish community in Palestine) that passionately and sincerely argued for Zionist policy to prioritise cooperation with the Arab population and for a bi-national state.

Rodinson called Judah Magnes one of the “few lucid minds” among the Zionist leaders (Arendt called him “the conscience of the Jewish people”) because he understood that without such a policy there would be violence and war (p68). So, while Rodinson was correct to say that “the seed of future conflicts" (p39) was sown at the start of the “colonising process”, he acknowledged that there were other Zionist voices that challenged official Zionism and its “Herzlian concepts” (p84). It was a historic tragedy that, for many reasons, including British imperialist tactics of divide-and-rule, those voices were eventually extinguished.

Rodinson was careful not to demonise the “colonisers”: “The Jews of Israel too are people like other people”. But he then sarcastically contradicts his own notion that these people were colonisers: “Many went there because it was the life preserver thrown to them. They most assuredly did not first engage in scholarly research to find out if they had a right to it according to Kantian morality or existential ethics. It is accordingly useless to reproach them for it” (p94).

Rodinson’s anti-colonialism is a far cry from the decolonisation movement of today. But the left-wing intellectuals of Boulevard Saint-Germain and Saint-Michel who from their café seats cheered on a “bloody solution” to the conflict were not so dissimilar. Rodinson captured their mood in his ironic questions to them about what should be done with these “colonisers”:

“Preach holy war against the intruders and demand that they be forcibly evicted and cast into the sea in the name of a universal conscience that was very slow to condemn colonialism? Brand them as criminals in the eyes of the whole world? Demand that, barefoot and with a rope already around their neck, they come pleading for forgiveness for their original sin?” (p92).

The sentiments of this earlier café society left are echoed in today’s decolonisation movement. Rodinson, in contrast, offered a way forward. He said that history is full of faits accomplis – Israel is one of them – over time people typically come to accept them. Such a resolution would depend on two conditions being met to leave the colonial situation behind. It would mean the Palestinian people “as a result of negotiated concessions” accepting Israel. It would also mean Israel recognising the wrong it did in creating a state for one people by displacing another.

Unfortunately we are further than ever from such a solution. However, it is worth remembering that this was the suggestion of an anti-colonialist with a deep understanding of the Middle East.

Stefanie Borkum completed her PhD in 2018 and after that vowed never to write anything longer than book reviews.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Radicalism of fools project.

The aftermath of the 7 October Hamas pogrom in Israel has made the rethinking of anti-Semitism a more urgent task than ever. Both the extent and character of anti-Semitism is changing. Tragically the open expression of anti-Semitic views is once again becoming respectable. It has also become clearer than ever that anti-Semitism is no longer largely confined to the far right. Woke anti-Semitism and Islamism have also become significant forces.

Under these circumstances I am keen not only to maintain this site but to extend its impact. That means raising funds.

The Radicalism of fools has three subscription levels: Free, Premium and Patron.

Free subscribers will receive all the articles on the site and links to pieces I have written for other publications. Anyone can sign up for free.

Premium subscribers will receive all the benefits available to free subscribers plus my Quarterly Report on Anti-Semitism (from April 2024). They will also receive a signed copy of my Letter on Liberty on Rethinking Anti-Semitism and access to an invitee-only Radicalism

of fools Facebook group. These are available for a 17% discounted annual subscription of £100 or a monthly fee of £10 (or the equivalents in other currencies).

Patron subscribers will receive the benefits of Premium subscribers plus a one-to-one meeting with Daniel. This can either be face-to-face if in London or online. This is available for a 17% discounted annual subscription of £250 or a monthly fee of £25 (or the equivalents in other currencies).

You can sign up to either of the paid levels with any credit or debit card. Just click on the “subscribe now” button below to see the available options for subscribing.

You can of course unsubscribe at any time from any of these subscriptions by clicking “unsubscribe” at the foot of each email.

If you have any comments or questions please contact me at daniel@radicalismoffools.com.