The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (Protocols) more than any other text captures the essence of anti-Semitism. It purports to be definitive proof of a Jewish conspiracy for world domination. For the Nazis, for example, it was regarded as a textbook for global conquest. Hitler even modelled his plans on it. In his words: “I saw at once we must copy it – in our own way of course. It is in truth the critical battle for the fate of the world” (Herman Rauschning, Hitler Speaks (1939). Quoted in Cohn 1995).

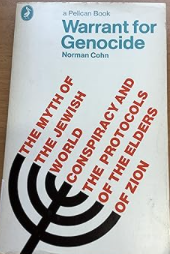

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975), a leading political thinker, argued the text was so influential that the key task was not to expose it as a forgery. It was instead to explain how it became “the text of a whole political movement”. In other words, it was to investigate why it was widely believed. That is the goal Norman Cohn (1915-2007), a British historian, took up in his classic book Warrant for Genocide: The myth of the Jewish world conspiracy and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion (1967).

The main strength of Cohn’s book is his exploration of the historical context in which the Protocolswas produced. He examines the political motivations of its producers and pinpoints the times its use had maximum effect. He goes a long way towards explaining how such a ludicrous myth could have had any plausibility and so much appeal. Cohn stops his history of the Protocols in 1945 with the end of the second world war. His book nevertheless provides a useful template with which to explore the life of the Protocols after 1945. For this reason the second part of this article looks at the work of Pierre-André Taguieff, a French philosopher, who takes up where Cohn leaves off. He shows why the Protocols is very much alive today.

The Protocols was written towards the end of the 19th century at the behest of the Okhrana, the Russian secret police in Paris. It was first published in Russia in 1903 as an appendix and then as a stand-alone pamphlet in 1905. It had precursors but the Protocols itself was a crude plagiarism of a French satirical work that had nothing to do with Jews (the Dialogue in Hell between Machiavelli and Montesquieu by Maurice Joly [1864]). It consists of 24 “protocols” or minutes from secret meetings held by the supposed leaders of “international Jewry”, the Elders of Zion.

Cohn usefully draws out three main themes that run through the rambling text. First, a critique of liberalism; second, an analysis of the methods to be used by the Jews to achieve world domination; and third the model blueprint of the world-state to be established.

He firmly grounds the Protocols and its precursors in their historical context – modernity. Cohn makes a compelling argument that the production and popularity of the Protocols have a direct relationship to the reaction against the far-reaching impact of modernity on European societies. The period from the late 18th to early 20th century, starting with the French revolution (1789), was characterised by the breakdown of traditional society, urbanisation and the development of industrial and finance capitalism. These profound changes took place at an unprecedented speed and had disorienting consequences. Religious and social hierarchies were rapidly dissolving, traditional norms were being called into question. New secular ideologies began to challenge the former binding values of religion – not only liberalism but anarchism, communism and socialism. Cohn’s description of the atmosphere of the times echoes the well-known phrase “[a]ll that is solid melts into air” (Marx and Engel’s Communist Manifesto of 1848).

How was social order to be maintained in newly liberalising and secularising mass democracies? Cohn shows that the producers of the Protocols and its precursors were reactionaries who, rather than embracing the promise of modernity, feared the threat it posed to the stability of society. The Protocolswas their political tool to stop or sabotage modernisation in order to cling on to the traditional societies that were being undermined. And they particularly wanted to prevent revolution and the spread of revolutionary ideas that would overturn that existing order.

It therefore makes sense that the Protocols was published in Russia in 1905 as political propaganda. Although the 1905 revolution failed, the State Duma (the Russian parliament) was established with the intention to transform semi-feudal Russia into a modern parliamentarian state. The Protocols tapped into the widespread anti-Jewish sentiment and galvanised people against the dangers of a supposed Jewish secret government – some members of the Duma were Jewish. The grain of truth in the lie made the Protocols plausible.

Cohn shows how all the tumultuous events of the modern age could be interpreted as benefiting the Jews and instigated by them. So Jews came to symbolise “the embodiment of modernity and its ills”. The Protocols mentions specifically the French revolution, Marxism and the international gold standard (the monetary system in which the value of each currency was pegged to gold). It even points to the 1892 Panama scandal in France which exposed the depth of parliamentarian political corruption. All these together were meant to illustrate the secret Jewish hand manipulating the world in order to disrupt and dominate it. However, it was vague and general enough to appear to prophesise all future events. It was a prism through which world history could be viewed, understood and predicted.

For Cohn the Protocols was only taken seriously outside of Russia after the Bolshevik revolution (1917), the murder of the Russian Tsarist family and the end of the first world war (1918). With the fear of world revolution on the horizon it began circulating throughout the world with a proliferation of translations and new prefaces to bring it up to date. Widespread anti-Semitism provided fertile ground for the delusional tale of Jewish global domination to flourish. It appeared plausible because there were a number of Jews playing a conspicuous part in European revolutions. And so the existence of a supposed Judeo-Bolshevik conspiracy became another “historical fact” the Protocols predicted. Jews would stop at nothing to cause chaos in the world in order to dominate it – they were capitalists and Bolsheviks at the same time. They were the symbol of all the evils of the modern world.

Cohn argues the Protocols was used as a political tool to sabotage modernisation and do damage to Jews who were portrayed as the root of all problems associated with modernity. He provides the modicum of fact that gave the fantasy its veneer of truth for those inclined to believe it. While the Protocols reflected events and trends of the period in which it was written it could also incorporate new developments. Cohn did not look at the life of the Protocols past 1945. But has the myth of the Jewish conspiracy disappeared? When I mention the Protocols to people they have either never heard of it or brush it off as a ridiculous nonsense that no one believes today. And yet Taguieff shows it is very much alive and exerts a pernicious influence.

During the 1980s, Taguieff was struck by the frequent mentions and uses of the Protocols when he was carrying out research into new forms of anti-Semitism. This observation led him to write Les Protocols de Sages de Sion: faux et usages d’un faux [The Protocols of the Elders of Zion: a forgery and uses of a forgery] (1992 with an expanded edition in 2004).

Taguieff shows how the success of the Protocols since the second world war is connected to the historical and geopolitical context. The Protocols shifted from Europe to the Middle East and this shift occurred because of a specific historical event – the creation of the state of Israel on 14 May 1948.

In the geopolitical context of the Middle East Tagueiff reveals how Nazi and Soviet propaganda inspired by the Protocols fused together to act as an effective political weapon in the hands of Arab leaders. Before the creation of Israel key Arab figures used the conspiracy theory of Jewish world domination to expose the Zionists’ “Satanic” plan in Palestine and to mobilise Arab support against it. The Protocols had been translated and published in Egypt in 1925 by a Christian Maronite priest but it was the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, who made it relevant to the Muslim Arab world of the 1930s. Often referred to as the founder of Palestinian nationalism, al-Husseini used this anti-Semitic forgery to illustrate the nefarious designs of the Zionists. In his view the Zionists were not only intent on destroying Christianity but also Islam.

Taguieff provides compelling historical details: the Grand Mufti became a close collaborator of the Nazis and was a loyal propagandist for them. After the second world war he eventually took refuge in Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Egypt. In 1956 another propagandist also took refuge in Egypt – the fanatically anti-Semitic Nazi Johann von Leers, a friend of the Grand Mufti. He was employed by Nasser’s Ministry of Information, in the Institute of Zionism Studies until his death in 1965. He played a role in the publication of a 1957 official edition of the Protocols. The introduction states that it is “the most important secret Zionist document” revealing the true objectives of “world Zionism”. “World Zionism” replaced “world Jewry”, or “international Jewry” – the language of the Nazis gave way to Stalinist vocabulary. Tagueiff demonstrates the amalgamation of Nazi and Stalinist propaganda in support of Arab nationalism. This amalgamation remains chillingly evident today.

Although the Soviet Union had initially supported the state of Israel it became clear that Israel was not going to fall under its sphere of influence in the Cold War. By the late 1950s it unconditionally supported several Arab nations against Israel. The anti-Semitic campaign against Soviet Jews initiated by Stalin escalated. Under the guise of anti-Zionism Soviet Jews were portrayed as traitors in league with imperialism and intent on destroying the Soviet Union. Zionism became the substitute for the old international Jewish conspiracy. All the old anti-Semitic stereotypes were transferred to the figure of the Zionist – conspiratorial, innately treacherous, mendacious, born to oppress and inherently evil. By the early 1960s the Soviet Union was producing propaganda in which Zionism was equated not only with imperialism and colonialism but also racism and Nazism.

After the Six-Day War (5-10 June 1967) Taguieff illustrates how the Protocols was used as a valuable political tool. Arab leaders urged their populations to read it “to understand their enemy” and “their Satanic programme and snake-like methods”. The preface to a new edition of the Protocols published in Lebanon a few months after the Six-Day War was subtitled: “The truth about Israel, its plans, its goals, revealed in an Israelite document”. This “Israelite document” was supposedly adopted back in1897 at the first Zionist world congress in Basle, Switzerland. Tagueiff says that the Protocols was used by the Arab states to deflect their humiliation. Their defeat at the hands of a tiny state was proof not of any incompetence or the corruption of their own leaders but of the authenticity of the Protocols. It had prophesised such an unnatural victory by a supernatural force.

Arab nationalists like Nasser and Islamists such as Sayyid Qutb of the Muslim Brotherhood used the Protocols in the 1950 and 1960s for political purposes. After the Six-Day War every new outbreak of conflict in the Middle East was followed by a massive circulation of the Protocols. Today, Hamas, the Palestinian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, quotes from the Protocols in their 1988 Charter. In 2007 Fatah, the Palestinian nationalist party in control of the Palestinian Authority said that theProtocols was required reading for its members (quoted in Taguieff 2024).

Both Cohn and Taguieff show that for over 100 years the Protocols has thrived in different contexts. These range from Tsarist Russia, the Third Reich and Stalin’s Soviet Union to the Arab countries and beyond following the creation of Israel. Past, present and future global political events can be interpreted through the prism of the Protocols. And so today for many the Israel/Gaza war is a story foretold in the Protocols. The worldview of the Protocols as a predetermined Manichean tale allows the avoidance of hard political analysis. Zionism is imagined as a Jewish conspiracy to dominate the world and the Zionist is essentialised as the embodiment of evil. The outlook embodied in the Protocols leaves little room for rational and valid criticism or serious consideration of any solution to a tragic conflict.

Stefanie Borkum completed her PhD in 2018 and after that vowed never to write anything longer than book reviews.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Radicalism of fools project.