How can the left be so blind to anti-Semitism among anti-Israel activists? Go on one of their marches – and I have attended several as an observer – and it appears blindingly obvious.

Yet most on what passes for the left nowadays, including Jewish anti-Zionists, staunchly deny its existence. Their typical rebuttal is that the charge of anti-Semitism is being cynically weaponised by Israel's supporters.

Not that everyone who goes on an anti-Israel protest is anti-Semitic. A significant proportion are gormless. However, the examples of anti-Semitism are legion. There are anti-Semitic placards, genocidal slogans, Hamas-style costumes, Islamist flags and swastikas (usually likening Israel to the Nazis). There are many expressing the old anti-Semitic canard that it is in the nature of Jews to kill children. And anyone who dares to carry a placard suggesting that Hamas are terrorists – which happens to be Britain’s official policy – faces swift attack by some protestors.

A widespread view on these protests is not simply that Israeli policy or its actions are open to criticism. Few would object to that in principle. It is rather that they see Israel as the epitome of evil in the world. It is seen as the ultimate symbol of the wickedness of apartheid, colonialism, imperialism and racism. There should be no doubt that these are hate marches.

Yet anti-Zionists, including a small number of Jews, seem oblivious to that fact. Take, for example, Natasha Walter, a British feminist Jewish writer. She wrote a piece in the Observer recounting her experience on going on one of the large anti-Israel protests in London. “On that day, once I joined the demonstration I realised that there was no need for me to feel nervous. I met up with a group of friends – from Jewish, Muslim and other backgrounds – and marched with them in the sunshine. It was much like any other big London demonstration, peaceful in the sense of being non-violent, but loud, crowded and passionate.”

She did then go on to acknowledge “there were some revolting placards I saw afterwards on social media”. But strangely they did not seem to register when she was on the march.

Walter then observes that “my initial apprehension that I might be walking into a situation where I would be unsafe was totally unfounded.” No doubt this is true. The small minority of Jews who ostentatiously take an anti-Israel position are indeed welcomed on such marches. They are widely regarded by the protestors as good Jews. This could even be called Jew-washing: the cynical mention of a small number of Jews on an anti-Israel protest to deny its rife anti-Semitism.

In contrast, the large majority of Jews who support Israel’s right to defend itself face threats and often actual violence. As someone who has also attended several pro-Israel counter protests I have seen the openly menacing behaviour of some anti-Israel protestors with my own eyes.

Those who for some reason cannot go on these marches can check out the excellent series of video reports by the Campaign Against Antisemitism. These do not prove that everyone on such marches is anti-Semitic. That is not the claim. No doubt some attend them in good faith. But there should be no doubt that is a significant anti-Semitic element on the protests.

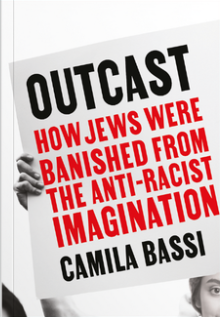

This all begs the question of how the left – or more precisely what passes for the left nowadays – can so vehemently deny the existence of anti-Semitism when it is so apparent. A new book by Camila Bassi, a lecturer in human geography at Sheffield Hallam University, provides a valuable service in answering this question.

The first part of the explanation is that the left tends to define anti-Semitism as hostility to Jews as Jews. For instance, an old-style far right activist, who condemned Jews for supposedly loving money would be rightly identified as an anti-Semite. But a leftist who framed his anti-Semitism in the thinly disguised form of hostility to Israel would not generally be recognised as such. It would, by this flawed definition, not be counted as Jew hatred.

It cannot be emphasised enough that the reference here is not to criticism of the Israeli government. Bassi herself, a supporter of the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty, emphases that she has disagreements with some of Israel’s actions. But she supports Israel’s right to exist alongside the right of Palestinians to have their own state. Her objection is to the common view among anti-Zionist activists that Israel is somehow the devil incarnate. Or, as she puts it, “Israel is irrationally and moralistically deemed the most harmful, deplorable and illegitimate nation state that must accordingly be destroyed” (p18). She then goes on to argue that Jews associated with Israel are expected by these activists to either condemn Israel or be damned.

To be fair some anti-Zionists concede that at the margins it is possible for anti-Semitism to be expressed in an anti-Israel form. But they fail to recognise that the demonisation of Israel is a central feature of contemporary anti-Zionism.

The other main flaw in contemporary anti-Zionist thinking is to understand racism in purely colonial terms. It sees racism as literally a black and white issue involving oppressed people of colour and those with white privilege. This view fits comfortably with identity politics which all too easily casts Jews as hyper-privileged. From there it is a small step to conceive of Israel as representing white privilege while the Palestinians are cast as the oppressed.

Yet the view that racism is an entirely black and white issue is completely ahistorical. It fails to recognise that racial thinking can take several different forms. It does not solely apply to how black people are treated by racists. Bassi gives as an example America’s Johnson Lodge Administration Act of 1924. That was the result of a campaign in the early twentieth century to exclude Italian, Polish, Russian and Jewish migrants to prevent “racial mixing” and deterioration. It that instance particular groups of white migrants were perceived to be a race apart from Americans.

Jews more generally have also historically been the subject of racial thinking. The Nazis, for instance, notoriously saw Jews as both sub-human and a powerful force conspiring to dominate the world. In that case Jews were perceived as racially apart from and inferior to Aryans. Yet proponents of identity politics to struggle to understand that it is not necessary to be a person of colour to be subject to racism.

This narrow view of racial thinking as solely an expression of colonialism not only leads to a blindness towards anti-Semitism. It actively contributes to the anti-Israeli form of Jew hatred. It upholds Israel not just as a colonial-settler state but as the exemplar of all the evils of colonialism. As Bassi puts it: “An understanding of Zionism as an especially deplorable colonialism, imperialism, nationalism and racism is commonplace on the academic and activist Left, as is the outright rejection of anti-Zionism as antisemitism” (p116).

The identitarian outlook also all too easily leads to the romanticisation of Islamist groups as heroic resistance movements. Groups, such as Hamas, which make overt anti-Semitic statements that would fit comfortably in Nazi propaganda, are somehow cast as heroic freedom fighters.

That then is what has happened to most of those who still identity as being somehow on the left. A political trend which, broadly speaking, supported freedom and national self-determination, while opposing racism, now all too often does the opposite. It may claim to oppose racism but it is among the most virulent proponents of anti-Semitism.

The aftermath of the 7 October Hamas pogrom in Israel has made the rethinking of anti-Semitism a more urgent task than ever. Both the extent and character of anti-Semitism is changing. Tragically the open expression of anti-Semitic views is once again becoming respectable. It has also become clearer than ever that anti-Semitism is no longer largely confined to the far right. Woke anti-Semitism and Islamism have also become significant forces.

Under these circumstances I am keen not only to maintain this site but to extend its impact. That means raising funds.

The Radicalism of fools has three subscription levels: Free, Premium and Patron.

Free subscribers will receive all the articles on the site and links to pieces I have written for other publications. Anyone can sign up for free.

Premium subscribers will receive all the benefits available to free subscribers plus my Quarterly Report on Anti-Semitism (from April 2024). They will also receive a signed copy of my Letter on Liberty on Rethinking Anti-Semitism and access to an invitee-only Radicalism

of fools Facebook group. These are available for a 17% discounted annual subscription of £100 or a monthly fee of £10 (or the equivalents in other currencies).

Patron subscribers will receive the benefits of Premium subscribers plus a one-to-one meeting with Daniel. This can either be face-to-face if in London or online. This is available for a 17% discounted annual subscription of £250 or a monthly fee of £25 (or the equivalents in other currencies).

You can sign up to either of the paid levels with any credit or debit card. Just click on the “subscribe now” button below to see the available options for subscribing.

You can of course unsubscribe at any time from any of these subscriptions by clicking “unsubscribe” at the foot of each email.

If you have any comments or questions please contact me at daniel@radicalismoffools.com.