It is hard to imagine a better illustration of the perils of Jewish anti-Zionism than Avraham Burg’s The Holocaust is Over. This is a man who was by any standard a leading figure in the Israeli elite. Yet, on the basis of some fundamental errors, lost faith in the Zionist project. It is a remarkable book in the worst sense of the term.

Avraham (often known as Avrum) Burg is as close as you can get to Israeli royalty. According to his own description he was “a man who was once at the heart of the Israeli establishment” (pxii). In 2000 he was acting president of the state of Israel. From 1999-2003 he was speaker of the Knesset (Israel’s parliament). He was also chairman of the World Zionist Organization, the umbrella body promoting the Zionist cause globally. During his army service in the 1970s he served as an officer in the elite paratroopers brigade.

In addition to his accomplishments both of his parents were, in their own way, exemplars of the Zionist story. His German-born father was an Israeli minister, representing the National Religious Party. His mother was a survivor of the 1929 Hebron massacre in which over 60 Jews were slaughtered in what was then British mandate Palestine.

Of course people often change their minds as they get older but Avrum Burg’s course reversal was particularly dramatic. It is also notable as he represents a small but significant section of Israeli Jewish society which has come to reject Zionism.

Such individuals have in turn given succour to the broader anti-Zionist movement worldwide. There is little anti-Zionist organisations savour more than quoting Israeli figures demonising Israeli society.

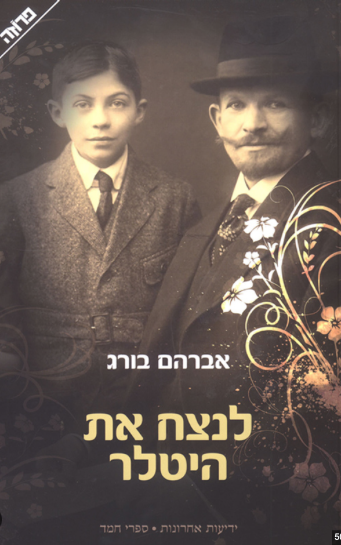

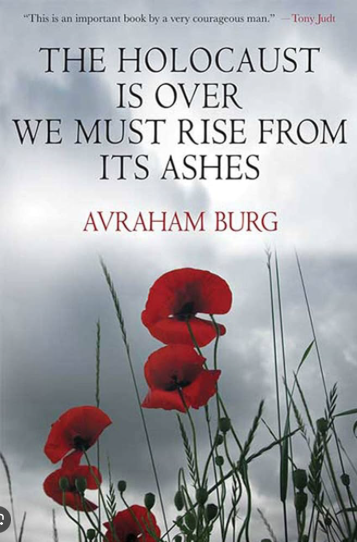

The core of Burg’s anti-Zionist argument is hinted at in the title of his 2007 book The Holocaust is Over: We must rise from its ashes. Essentially his argument is that Israel should get over what he sees as its unhealthy obsession with the Holocaust. The argument is perhaps even clearer in the title of the Hebrew edition, published the previous year, which can be translated as “Defeating Hitler” (see cover below).

It is undoubtedly true that Israel is still in some respects haunted by the Holocaust. Yom HaShoah (Israel’s Holocaust Memorial Day) is an important annual event in the Israeli calendar. Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust remembrance centre, is regularly visited by school children, soldiers and others.

It is also the case that Israeli politicians see shadows of the Nazis in their current enemies. For example, Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s prime minister, has referred to Hamas as “new Nazis”.

But Burg’s response to the shadow of the Holocaust seems to be that Israel should simply get over it – unhelpful advice for anyone suffering from severe trauma. He concludes one of his chapters by saying that Israel should overcome Hitler’s evil legacy.

But such a framing of the argument blurs the crucial distinction between what Hitler did and how Israel reacts to it. Some key elements of Israeli memory are indeed a reaction against Hitler’s legacy but that does not make it somehow defined by the Nazi dictator. Or as Burg claims in his book “sixty years after his suicide in Berlin, Hitler’s hand still touches us” (p23).

Nor are parallels between the Nazis and groups such as Hamas as outlandish as Burg’s argument suggests. Of course Hamas is not literally identical to Hitler’s Nazi party. The context is entirely different. Nevertheless, the Islamist group, along with its allies, has openly pledged time and again to destroy Israel. This is a reality to which anti-Zionists such as Burg seem oblivious. If anything they dismiss any rational discussion of the subject with accusations of Islamophobia.

If this was not clear 20 years ago, when Burg’s book was first published, it should be abundantly apparent in the wake of the 7 October pogrom. Hamas leaders have pledged time and again to repeat their atrocities. They have also received considerable backing from Iran, Qatar, Turkey and other Islamist groups. Yet anti-Zionists ignore this reality.

Anti-Zionism seems to be defined by a phoney universalism that obliterates what is specific about the Jewish experience. For example, Burg refers to holocausts in Armenia and against the Herero people in southern Africa in the early 20th century. While these were without doubt terrible events Burg and others are wrong to liken them to the Holocaust.

As I have argued previously anti-Semitism can be seem as the perception that Jews embody the supposed evils of the modern world. It was from this premise that the Nazis attempted to annihilate Europe’s entire Jewish population. The drive to totally obliterate a people from the face of the earth makes it stand out from other instances of mass killing.

It would indeed be welcome if Israel could escape from under the shadow of the Holocaust. But that cannot be achieved by demanding that the country should simply get over it. The pre-condition is a world in which Israel no longer faces an existential threat from its enemies. Only then can it escape from the terrible legacy of anti-Semitism.

Avraham Burg. The Holocaust is Over: We must rise from the ashes. Palgrave Macmillan 2008. (Originally published in Hebrew as Victory over Hitler in 2007).

Burg also has a current substack.