Two recent stories highlight some of the misconceptions that are often associated with Holocaust education.

Perhaps the most astonishing involved the Anne Frank Trust; an organisation whose name – linking it to perhaps the best-known victim of the Holocaust - makes it sound unimpeachable. Yet it issued an unreserved apology after reports that one of its workshop facilitators, a freelance arts practitioner, had made anti-Semitic comments in the past. The trust described the affair as “a failure in due diligence”.

The Jewish Chronicle (the JC), one of the main Jewish community publications in Britain, took a more critical view. According to its investigation the activist had compared Jews to Nazis and justified rocket attacks by Hamas, the Islamist organisation that controls Gaza, against Israel. She also referred to “Zionist scum”.

In the newspaper’s view it would be wrong to see the affair as a simple lapse of judgement.The JC said it fitted into a pattern of the Anne Frank Trust allowing “speakers with a history of incendiary statements about Israel and Jews”.

The second story involved the ongoing row over the proposed Holocaust Memorial and Learning Centre in Westminster. Some of the disagreements relate to problems getting planning permission on the site as it would mean the loss of a green space in central London. Others have argued it could be a security risk as it could be a target for protestors or vandals.

But there are also political disagreements related to the message being propagated by the exhibition. Prominent members of the Jewish community are among those objecting. For example, Melanie Phillips, a prominent Jewish journalist, has argued that the project would equate Holocaust victims with those killed in conflicts elsewhere.

These two stories along point to some of the related problems associated with the current discussion of the Holocaust:

· The relativisation of the Holocaust. It is a serious problem that the Holocaust is often mentioned in the same breath as, for example, wars in the former Rwanda (1994) and Bosnia (1995). That is not to deny the other conflicts were tragic but rather to argue that they were completely different in character to the Holocaust. The large numbers of civilians killed in Yugoslavia and Rwanda perished in what were essentially bloody civil wars. The Holocaust, in contrast, involved one of the most developed western powers invading surrounding countries and systematically setting out to murder Jews.

· In this context it is worth noting that Britain’s official Holocaust Memorial Day is officially defined in the following terms: “On Holocaust Memorial Day, we remember the six million Jews murdered in the Holocaust, and the millions of people killed under Nazi persecution of other groups, and in the genocides which followed in Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia, and Darfur.” This is a deeply ambiguous statement. On the one hand, it distinguishes the Holocaust from what it defines as other genocides but, on the other hand, they are all commemorated under the rubric of Holocaust Memorial Day.

· The child’s eye view. It is striking that much Holocaust education involves looking at the tragedy through the eyes of children. For instance, lessons related to Anne Frank in schools are often linked to discussions about tackling bullying. Whatever the intentions of the teachers who run such lessons this approach can only trivialise the Holocaust. Bullying can no doubt be a problem in schools but it is absurd to compare it to genocide. Even to argue that it is simply the start of a process that can lead to mass murder in the future is crass.

· The Holocaust as the outcome of extreme prejudice. A point related to the one above is to simply see the Holocaust as the result of extreme prejudice. From that perspective teaching children to behave well and respect others can become part of Holocaust education. Such an approach strips the Holocaust of its specificity. To simply view it as the outcome of extreme prejudice is to lose sight of its historical drivers. For example, see this initiative from the National Holocaust Centre and Museum.

· The instrumentalisation of the Holocaust. Too often the Holocaust is not discussed in its own terms but rather as a way of justifying other things. For example, the need to restrict freedom of speech in certain instances, the need for individuals to behave well towards each other or the importance of having a benign policy towards refugees. It would be far better if the focus was on understanding the unique character of the Holocaust in its own terms. Yet this tends to get lost in the contemporary discussions.

A critical article, by Edward Rothstein, a critic at large at the Wall Street Journal, in Mosaic magazine on “The problem with Jewish museums” raises many of these issues. One of his comments about the misuse of Holocaust history in an exhibition on Anne Frank at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles is apt more generally: “Thus is history distilled into tripe, horror into effervescent inanity. Out of the history of the Holocaust, the museum teases unconvincing homilies to the effect that the root cause of genocide is prejudice and intolerance—by now an international delusion. The impulse to tell the Holocaust story only in the context of such elaborate generalizations is also what has helped justify its inclusion in school curricula and win public financing for museums. The Museum of Tolerance obliges with its own series of educational programs, including ‘Tools for Tolerance for Professionals’: sensitivity training for educators, law-enforcement officers, and corporate leaders. The history that emerges from all this is history stripped of distinctions: that is, no history at all.”

Postscript: Holocaust museums in Britain

There are hundreds of Holocaust museums around the world. Most of them were not established in the years following the Second World War but substantially later (It is also worth noting that the first Holocaust Memorial Day in Britain was introduced as relatively recently as 2001). Many of them have education centres attached to them.

The main Holocaust museums and memorials in Britain are as follows but there are many smaller ones too. I have put them in the chronological order in which they are established.

The Wiener Holocaust Library in London. This grew out of the collection of Dr Alfred Wiener; a Germany Jew he fled Nazi with his family in 1933.

The Holocaust Memorial in London’s Hyde Park. Constructed in 1983 and paid for by the Board of Deputies of British Jews.

The National Holocaust Centre and Museum in Nottinghamshire. Founded in 1991.

The Holocaust exhibition and learning centre founded in 2018 in partnership with the University of Huddersfield. In the process of being rebranded as the Holocaust Centre North.

The Imperial War Museum Holocaust Galleries. Opened in 2021 in London.

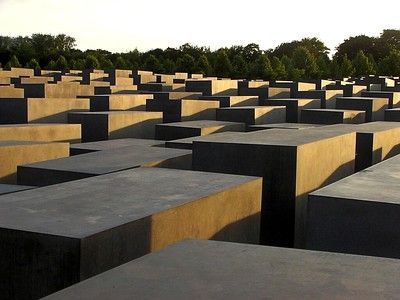

Photo: "Holocaust memorial Berlin" by d.i. is licensed under CC BY 2.0.